Early Career Occupational Hygienist Essay Award 2024 – Heather Campbell

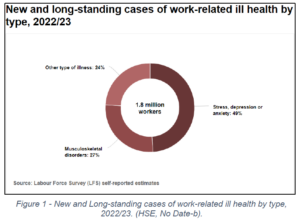

Work related mental ill-health is defined by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) as, ‘a harmful reaction … to undue pressures and demands … at work,’ (HSE, No Date-b). Mental health conditions such as depression, stress, and anxiety are the leading causes of work-related ill-health in the United Kingdom.

(Figure 1, (HSE, No Date-b).

The causative mechanism of mental ill-health is recognised to be complex, and multi-faceted. There are many external and non-work-related factors which can contribute to the mental health status of an employee. However, regardless of whether a condition is caused or aggravated by work, employers have legal responsibilities to assess and control risks to their employees, which may negatively affect their mental health. An example of this is completing a work-related stress risk assessment, and taking action to reduce stress to that employee, so far as is reasonably practicable, (HSE, No Date-c).

‘Psychosocial risks’ are risks to mental health which include: mismatches in skills, excessive work demands, unsociable or lengthy work hours, unsafe working conditions, bullying, harassment, discrimination, job insecurities and pay, organisational structure issues, unclear job roles, and lack of support, (WHO, 2022). These are all risk factors for workplace mental ill-health which should be identified, assessed, and controlled by employers.

The incidence of sickness absence from stress, depression or anxiety has increased dramatically over time, (HSE, 2023). 12 billion working days are estimated to be lost every year, as a result of depression and anxiety, on a global scale, (WHO, 2022). In the UK, absenteeism due to work-related mental ill-health was estimated to have resulted in 17.1 million working days lost in 2022/23, (HSE, 2023).

It is evident that improvements in mental health outcomes are in the employers’ interests. This would have dual benefits of working to execute their legal duties to protect their employees from work-imposed risk factors, and to avoid the high business costs associated with poor mental health, by reducing days lost, and unproductive work by employees attending work unwell.

Such costs may be incurred from absenteeism, (i.e., employees not attending work due to illness), or, from other, more difficult to quantify costs, such as from presenteeism and leaveism.

‘Presenteeism’ is where employees attend work unwell, impacting their productivity – as they are not working to their full potential, (Hesketh, 2024).

‘Leaveism’, is associated with behaviours such as regularly working extra hours, using leave entitlements as sickness absence or for caring responsibilities, (Hesketh, 2024). Such behaviours have increased in prevalence since the advent of hybrid working, post-COVID-19 pandemic – blurring the lines between home and work, (CIPD, 2020). Leaveism behaviours are commonly linked to ‘burnout’ – a cited as a risk factor for depression, anxiety, and physical illness (including musculoskeletal disorders and cardiovascular disease), (Ahola, 2007).

Costs to the public sector are also high and are estimated to be greater than the private sector, (Frost, 2011), from subsidiaries to employers to help cover sick pay, costs to the NHS and also from benefits related payments where persons are considered unfit for work due to disabling health conditions.

The Effects of Occupational Hygiene on Mental Health

Occupational hygiene aims to prevent work related ill-health through controlling workplace health hazards. The discipline is often advisory in nature, with competent assistance engaged by employers to assist them in executing their legal duties, under the Health and Safety at Work etc Act (1974).

The role of an occupational hygienist extends to education, recommendation and advice to employers and employees alike, based on their observations, measurements, assessment, and evaluation of health hazards in a workplace. Successful occupational hygiene practice results in employer’s implementing proportionate and reliable control measures and adopting working practices, which prevent, or adequately control exposure to health hazards in the workplace. To be fully effective, buy-in from employees is required, to make sure those controls are adhered to and properly applied.

Effective communication between the occupational hygienist and relevant parties, (such as the employer, employees, and safety representatives), is key (BOHS, No Date). Good communication and consultation promotes buy-in and participation from relevant parties, and aims to ensure that the workforce and employer understands the nature of the risk, what the health effects are, and why control options have been recommended or implemented to protect health.

Various aspects of the hygienist’s evaluation and control process should involve the consultation of employees, as they are the people who are conducting the work, using the equipment, and are potentially at increased risk of exposure from processes. Feeling a lack of control over job design, is a known psychosocial risk factor for mental ill-health, (WHO, 2022), which may be overcome to some degree, where worker consultation can input into hazard controls, and design of work processes. This results in dual benefits in risk management, to both mental and physical health. Consultation ideally results in control options and work processes being developed in consultation with the people who are intimately familiar with the process, giving more control over the work, and higher likelihood that the controls will not be bypassed, due to unforeseen issues, such as maintenance.

Another documented risk factor for mental health at work, is exposure to unsafe or poor working conditions, (WHO, 2022). Workers who are subjected to unsafe working conditions are likely to be exposed to occupational health hazards, in absence of good occupational hygiene, increasing their risk of developing work-related ill health. This includes chronic work-related ill-health conditions from exposure to chemical and physical hazards, and mental ill-health from chronic ill-health outcomes and lack of control over the work.

Good occupational hygiene aims to prevent the development of chronic ill-health conditions, however in its absence, uncontrolled exposure to workplace health hazards can result in disabling and irreversible conditions, which are associated with: poor quality of life, poor mental health, disability, early morbidity, and financial and social issues.

Figure 2 – Cutting stone without dust suppression example photograph. (HSE, 2020)

Silicosis is an example of such a disease – which is associated with exposure to respirable crystalline silica (RCS), an airborne contaminant commonly associated with processes in foundries, stonemasonry, and construction. The condition affects lung function from fibrosis of the lung tissues, (HSE, 2024), and can result in premature death, following increasingly debilitating respiratory symptoms, (HSE, No Date-a). Studies have shown that depressive symptoms are highly prevalent in patients with silicosis, (Wang et al., 2008). These outcomes are speculated to be a result of negative impacts on quality of life from the illness, which in many cases, is preventable, if good occupational hygiene principals are applied. Despite this, death still occurs as a result of silicosis, with 14 deaths reported in 2006, and 7 reported in 2007, (HSE, No Date-a).

There are many other chronic occupational ill-health conditions which may arise from poor occupational exposure control, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), occupational asthma, occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis (OHP), hand arm vibration syndrome (HAV), and noise induced hearing loss (NIHL). All these chronic ill health conditions have the potential to affect mental health outcomes from their debilitating and isolating effects on the sufferer’s life.

‘Good work is good for health’, (Frost, 2011), and health outcomes, including mental health, are improved for people who are in ‘good’ work. Resulting disability from chronic ill-health may render a person unfit to work any longer, with lower employment rates associated with people suffering from long term health conditions, (Frost, 2011). Being unable to work as a result of long-term ill-health may have an additive effect on mental health outcomes, from decreased quality of life, financial concerns, isolation, social networks, and reduced self-esteem. All having the potential to contribute to poor mental health, however, the original chronic ill-health may have been preventable, were good occupational hygiene applied proactively.

In the informal economy, and in parts of the world which are outside of regulatory protections, (ILO, 2018; WHO, 2022), there is a greater prevalence of poor working conditions, with little alternative for employment due to financial and social factors, (ILO, 2018). Occupational hygiene is not afforded, or accessible in many of these workplaces, and the control measures which are required for adequate control against many hazards in these professions, are not applied. As a result, there is increased exposure of employees in these workplaces to psychosocial, physical, and chemical health hazards, increasing the risk of both mental and physical ill-health because of their work.

Recent research has supported that prevention of ill-health conditions in the workplace through improved work environments, also positively supports worker wellbeing, (BOHS, 2019; Fan, Mustard and Smith, 2019). Better mental health outcomes were found to be associated with higher levels of job control, social support, and job security, (Fan, Mustard and Smith, 2019).

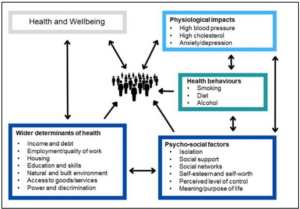

Figure 3 – System map of the causes of health inequalities (adapted from the Labonte model).(OHID, 2022; PHE, 2021)

Moreover, workplaces where good occupational hygiene is absent are likely to comprise of lower socioeconomic status (SES) employees, with wider determinants of health already at play, and a pre-existing relationship between low SES and poor mental health outcomes already acting as a precursor to poor mental health (Kim and Cho, 2020; OHID, 2022). Targeting work related stressors, is evidently important in such workplaces, where employees may be at increased risk from external or pre-existing factors.

Conclusion

In summary, occupational hygiene by extension has the potential to have huge impacts on worker health through a variety of aspects. Not only does occupational hygiene reduce the risks associated with physical ill-health conditions, but, by extension, this can prevent the mental ill health outcomes associated with chronic ill health, disability, and poor working environments.

Good occupational hygiene which considers the views of operators and employees involved in processes can also influence feelings of control of the work process, improve morale through better working conditions, and promote feelings of organisational support and positive culture, where employer buy-in is engaged.

Good occupational hygiene can work as part of a robust health and safety management system to reduce some of the risk factors in workplaces which are effect mental and physical health, ultimately improving the health and wellbeing of employees.

References:

1. Ahola, K. (2007). ‘Occupational burnout and health’.

2. BOHS (2019). ‘Good work environments don’t just prevent mental illness, they also promote positive well-being’ British Occupational Hygiene Society Available at: https://www.bohs.org/media-resources/press-releases/detail/good-work-environments-dont-just-prevent-mental-illness-they-also-promote-positive-well-being/.

3. BOHS (No Date) What is Occupational Hygiene? Online BOHS [Webpage]. Available at: https://www.bohs.org/information-guidance/what-is-occupational-hygiene/#:~:text=Occupational%20hygiene%20is%20the%20discipline%20of%20protecting%20worker%E2%80%AFhealth,worker%20well-being%20and%20safeguarding%20the%20community%20at%20large. (Accessed: 28/06/2024 2024).

4. CIPD (2020) Managing the challenge of workforce presenteeism in the COVID-19 crisis. online CIPD [Webpage]. Available at: https://www.cipd.org/uk/views-and-insights/thought-leadership/cipd-voice/managing-challenge-workforce-presenteeism-covid-19-crisis/ (Accessed: 21/05/2024 2024).

5. Fan, J. K., Mustard, C. and Smith, P. M. (2019). ‘Psychosocial Work Conditions and Mental Health: Examining Differences Across Mental Illness and Well-Being Outcomes’ Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 63 (5), pp. 546-559 https://doi.org/10.1093/annweh/wxz028.

6. Frost, D. C. B. D. (2011). Health at work – an independent review of sickness absence The Stationary Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/181060/health-at-work.pdf.

7. United Kingdom, The Health and Safety at work etc. Act (1974).Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37/enacted.

8. Hesketh, C. C. I. (2024). ‘‘Leaveism’ and ‘presenteeism’ continue even when employers are more flexible – here’s how to be happier at work’, The Conversation, 03/01/2024. Available at: https://theconversation.com/leaveism-and-presenteeism-continue-even-when-employers-are-more-flexible-heres-how-to-be-happier-at-work-219190 (Accessed 21/05/2024).

9. HSE (2020). CIS36: Construction Dust Online HSE. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/cis36.pdf.

10. HSE (2023). Historical picture statistics in Great Britain, 2023. Online: HSE. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/assets/docs/historical-picture.pdf.

11. HSE (2024). Control of exposure to silica dust. A guide for employees. Online: Health and Safety Executive Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg463.pdf.

12. HSE (No Date-a) Silicosis Online: HSE [Webpage ]. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/lung-disease/silicosis.htm (Accessed: 09/02/2024 2024).

13. HSE (No Date-b) Work-related ill health and occupational disease in Great Britain. Online. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/index.htm (Accessed: 21/05/2024 2024).

14. HSE (No Date-c) Work-related stress and how to manage it. Online: HSE [Webpage]. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/risk-assessment.htm (Accessed: 21/05/2024 2024).

15. ILO (2018). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture. 3rd Ed. edn. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-picture-third-edition.

16. Kim, Y. M. and Cho, S. I. (2020). ‘Socioeconomic status, work‐life conflict, and mental health’ American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 63 (8), pp. 703-712.

17. OHID (2022) Guidance: Health disparities and health inequalities: applying All Our Health. Online: Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (OHID). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-disparities-and-health-inequalities-applying-all-our-health/health-disparities-and-health-inequalities-applying-all-our-health (Accessed: 28/06/2024 2024).

18. PHE (2021) Guidance: Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities: main report. Online: Public Health England (PHE). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-inequalities-place-based-approaches-to-reduce-inequalities/place-based-approaches-for-reducing-health-inequalities-main-report (Accessed: 28/06/2024 2024).

19. Wang, C., et al. (2008). ‘Depressive symptoms in aged Chinese patients with silicosis’ Aging and Mental Health, 12 (3), pp. 343-348.

20. WHO (2022) Mental Health at Work Online: World Health Organisation (WHO) [Webpage]. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work (Accessed: 28/06/2024 2024).